Even though Dr. Jonathan Lundgren had won several

awards and published hundreds of scientific articles, he was reprimanded and

treated with hostility for expressing the findings of his research on the ways

neonicotinoids harm bees and monarch butterflies. In 2016 Jonathan Lundgren

left his job at the USDA and began a fifty-acre farm: Blue Dasher Farm; he named it after his favorite dragonfly.

Dr. Jonathan Lundgren also created the Ecdysis Foundation, a non-profit research lab located on the farm. The name of the

foundation refers to the stage of metamorphosis in which insects shed their

skin.

Several farmers support his research and

partner with him to create a community of farmers who are interested in

sustainable practices that work to improve the quality and resilience of the

soil. In doing so, they restore the integrity of ecosystems, curb climate

change, improve the quality of water and air and support human health. What is

not to like about that?

Kristin

Ohlson reflects on their partnership in practical terms: “All these farmers are

citizen-scientists. They walk the land with the informed, fond curiosity of

naturalists and know that it’s folly to approach their work as if they were

baking the same cake every season using the same recipe and ingredients. They

know that nature has many moving, changing, interacting living parts and that

these parts need our respect. For the farmers trying to find a path to both

healthy profits and healthy landscapes, Lundgren’s science can answer some of

their questions about how to proceed.”

Buz Kloot is a scientist at the University of

South Carolina who used to hate his work because he felt like a coroner. “The

waterways were dying and the only thing I could do was to declare the cause of

death.” He did not think that anything could change because he did not

think farming could change. He did not think the health of the soil in modern

America’s farmlands could change until he visited a farm owned by a soil-health

pioneer: Ray Styer.

Ray Styer had not used chemical fertilizers

in twenty-five years.

You can learn more by listening to Dr. Buz Kloot

here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kWDO_O3JUSI

The experiences of various farmers are

featured in the chapter entitled “Agriculture that Nurtures Nature”. It is the

fifth chapter of Sweet in Tooth and Claw by Kristin Ohlson.

I appreciate how the author debunks the false

assumption that more agricultural productivity is needed to satisfy the demands

of a growing population. “According to the Food and Agriculture Organization

of the United Nations, we already grow enough to feed ten billion people, which

is one estimate of the world’s peak population. A third of that production goes

to waste, and another third feeds automobiles and CAFOs—Concentrated Animal

Feeding Operations are where animals are divorced from their natural surroundings,

crammed into very small spaces, and often fed things they never evolved to eat.

The massive amount of food produced by industrial agriculture rarely reaches

the billion people who are hungry, not because there isn’t enough food, but

because it’s too expensive or is not locally available. And the farmers who are

on the industrial-production treadmill suffer, too: the problem for them is

overproduction, which results in lower prices despite their hard work”.

Why has

cooperation in the natural world been overlooked for so long?

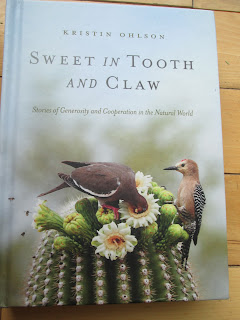

Sweet

in Tooth and Claw delves into the ways cooperation in the natural world works to sustain life.

Her exploration of scientific facts may help readers understand why it is

necessary to learn these concepts and may inspire societies to emphasize

cooperation.

The facts she shares in her books corroborate how

our lives are interdependent and connected. To illustrate the awareness on the essence of her message, I can cite beavers and focus on how

their actions benefit the environment.

Many

people do not know anything about the unique role beavers play through their sophisticated work. Beavers help to minimize the effects of floods, and they even help

to prevent them. Beavers improve the quality of the water, store water during

droughts, and create wetland habitat for other species, enhancing biodiversity.

How does our own survival depend on the integrity

of life on earth? How can our choices help to make a difference? Sweet in

Tooth and Claw is a comprehensive resource to answer these questions.

If you

don’t have time to read the whole book, I recommend the chapters entitled “Living

in Verdant Cities” and “We are Ecosystems”.

Perhaps you remember that 90 percent of

vascular plants interact with fungi. Their exchange plays a role in their

health and survival, but these interactions are often ignored. I wrote about

this here.

There are more living organisms in a teaspoon

of healthy soil than human beings on earth, and understanding this web of life

is a work in progress.

When soil is healthy it is better prepared to withstand unexpected phenomena such as droughts and floods. Sustainable practices of agriculture that are based on fostering biodiversity and enriching the health of the soil with organic matter rather than using synthetic chemicals are reasonable ecological strategies to face the challenges ahead.

I

highly recommend Kristin Ohlson’s Sweet in Tooth and Claw. Some of the

topics she addresses in this book have been discussed in previous posts at My

Writing Life blog.